There lived in a tree with his family of nine,

A little brown squirrel with the name Johnny-mine.

This name was just perfect, for as you will see,

He thought he owned everything, even the tree.

Whenever he played with his friends from the plain,

He tried to lay claim to the nuts, leaves, and rain

He found on the ground. But, his friends didn’t mind.

“There’s just so much stuff, he can have it,” they chimed.

The squirrel Johnny-mine wasn’t better at home.

He squeaked all the time in that high-wheezy tone:

“That’s mine … no that’s mine … let me have it right now …

Give me all the nuts or I will have a cow!”

His parents who loved him saw how he behaved.

They gave him the name, “Johnny-mine,” and it stayed.

The squirrel didn’t mind, for he knew what it meant.

He knew it was true. He was intelligent.

One day all his brothers and sisters complained,

“Oh, mom, can’t you do something soon,” they refrained.

“If he says, ‘that’s mine,’ one more time we will die!”

His mother said softly, “I’ll just have to try.”

“Dear, Johnny-mine, listen to what I will say,”

Said Johnny-mine’s mother the very next day.

“You just have to stop all this nonsense right now!

Come out of our house and I’ll show you just how.”

She took Johnny-mine on a walk ’round the tree.

“Just look at the leaves, nuts and water you see.

There’s plenty for all, so there’s no need to say,

‘I own everything.’ Now please go off and play.”

Well, Johnny-mine thought as he looked all around,

“It’s really so cool all this stuff on the ground.

I’ll have even more if I start right away

To gather them up.” He worked all through the day.

He gathered the nuts in a pile, then two.

He gathered the rain and he gathered the dew.

He gathered the leaves into mounds soft and pure.

He gathered them up. They were his, he was sure.

Now, Johnny-mine’s parents watched him from within

Of their home. And they thought, “Where do we begin?

We taught him to think grateful thoughts and to share.

Why is it that our Johnny-mine doesn’t care?”

While Johnny-mine gathered his treasure, there came

Into the squirrel’s yard an old turtle, so tame.

“Hello, there, young fellow,” the old turtle said.

He smiled at Johnny-mine and then bowed his head.

“I see that you have many nuts at your feet.

I’m hungry. May I please have something to eat?”

“They’re mine,” said the squirrel, as he plopped on the ground.

“Why should I give you some?” he said with a frown.

When Johnny-mine’s parent heard this they ran out,

And said, “Johnny-mine, now what is this about?

This friendly old turtle needs kindness from you,

Why do you deny him? This cannot be true!”

“You give him a nut and some water to drink!

Now Johnny-mine share! Oh, do you really think

That this is all yours! No! We’ll take it away!”

They made their boy give without any delay.

The turtle said, “Thank you,” and then he ate well.

And when he had finished he lifted his tail

And pointed to all of the nuts, leaves and rain

The little squirrel Johnny-mine guarded again.

“I think it is nice all this work that you’ve done.

You’ve been kind to me, and I hope you have fun.”

Then turning to Johnny-mine’s parents he said,

“Do not punish him. Do not fill him with dread.”

“You really can’t fault him,” he said moving near,

“Because Johnny thinks he owns everything here.

You call him a name that each day reminds him

Of just what he does,” said the turtle to them.

“Then how do we teach him that he does not own

The nuts, leaves and rain that he finds ’round our home?

Maybe it is best if we take them away

Whenever he’s greedy, like he is today.”

The wise and old turtle thought hard and with care.

He knew that the parents were full of despair.

He looked at the boy and his parents, and then

He looked at the tree and the boy once again.

“I’ll ask you a question, my friend. Think real hard

As you look around at these things in the yard.

Do you, Johnny, know from where all of this came —

The nuts and the leaves and the gentle spring rain?”

The squirrel, Johnny-mine, knew just what he would say.

“I gathered them up. Why, I did it today!

I gathered the nuts and the leaves you see here!

I gathered the rain that I treasure so dear!”

The old turtle smiled and then he asked again,

“Before you did work, where did it all begin?

Look up in the tree and tell me what is there?”

The old turtle said, with his tail in the air.

The little brown squirrel looked up into the tree.

He looked and he said, “My, can this really be?

The tree is so full of the nuts that we eat!

And look at the leaves for our home, this is neat!”

“They come from above, all the blessings we know,”

Replied the wise turtle. “It really is so.

And think of the rain as it falls from the sky.

It comes from above. Do you even know why?”

Now, Johnny-mine had to think hard once again,

Though finding the answer came not from his brain.

It came from his heart as he looked up above.

“Why, all that I have is a gift of true love.”

The old turtle nodded and said to boy,

“Don’t ever forget this great lesson of joy.”

And then to his parents, the turtle did say,

“You have a good son. Call him ‘Johnny’ today.”

He bid them goodbye with a wave of his tail,

And walked down the path as the sun slowly fell.

And when he was gone, the squirrel Johnny then said,

“These nuts are not mine, but our family’s instead.”

And so little Johnny learned something that day,

That stayed in his mind when at home and at play.

He learned that the nuts and the leaves that he shares

Are not his but are a gift from One who cares.

Are we all like Johnny-mine, thinking we own

The nuts or the leaves or the rain that we’ve sown?

Or do we feel deep in our hearts of the love

That comes out of Heaven, as gifts from above?

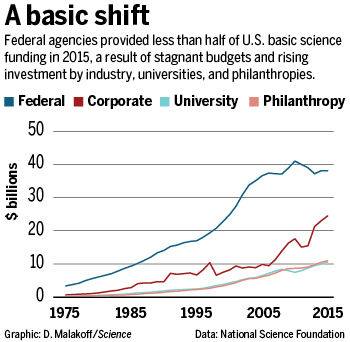

The fact is, funding from government for basic research at universities has stagnated in recent years. Currently, as reported in a Science magazine story,

The fact is, funding from government for basic research at universities has stagnated in recent years. Currently, as reported in a Science magazine story,  In an essay published in 1970 in the New York Times Magazine, Friedman wrote that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” which has become known as the

In an essay published in 1970 in the New York Times Magazine, Friedman wrote that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits,” which has become known as the

Had a fascinating presentation today in my agricultural ethics course by

Had a fascinating presentation today in my agricultural ethics course by  Dr. Bonnot also talked about

Dr. Bonnot also talked about  You are taking a college course. Near the end of the semester, the professor reminds the class that the final exam is worth 100 points and is scheduled for the day and time specified by the University. The professor then says there are two options for the final exam.

You are taking a college course. Near the end of the semester, the professor reminds the class that the final exam is worth 100 points and is scheduled for the day and time specified by the University. The professor then says there are two options for the final exam.